Simon was raised in Thuringia with the name of Anton. Father was a blacksmith. Even as a child Simon wore girls’ clothes whenever possible, and was pleased to do housework for mother. At age 17 Simon volunteered for the cavalry to avoid service in the infantry where his ‘girlish’ gait would be mocked, but was mocked anyway. After three years of service, Simon became a machinist in a bicycle factory. A marriage to a woman in 1908 resulted in five children. Simon worked in breweries and tanneries, went to sea as a stoker and herring fisherman, and worked as a bridge builder in northern cities such as Kiel, Wilhelmshaven and Bremen. When the war started in August 1914 Simon was running a business selling newspapers and maps – which was taken over by his wife when he was conscripted. After 1918 Simon opened a restaurant in the Ruhr area, and in 1923 opened Café 4711 in Essen's Segerothstraße, which also acted as a “neuer Damenklub” for Essen’s transvestites. Herr and Frau Simon separated in 1927 and their divorce was finalised in 1932.

Simon was arrested several times for illegal beer sales from the secret bottle cellar of Café 4711. In August 1929, Simon was summoned to appear before the Essen district court, and appeared in women's clothes. The judge found this "improper", and imposed an administrative fine of 100 marks. Simon's appearance caused a stir not only in the Ruhr press, but also in the Berlin transvestite scene. Simon wrote an account which appeared in the magazine Die Freundin (The Girlfriend – a lesbian magazine with trans content) asking whether he should appear again "als Dame (as a lady)" at the next trial. A reader from Upper Bavaria, who would also "rather be a woman", expressed indignation at the judgement of the Essen district court and recommended that Simon obtain official permission to wear female clothing, a Transvestitenschein. |

| Toni Simon in the 1930s |

In June 1930 Simon had written to the Friedrich Radszuweit (1876-1932) publishing house advising against a new magazine especially for transvestites in that "A transvestite doesn't read a transvestite magazine, because he'd rather spend his money on nice stockings".

By then Simon was undergoing a deep personal crisis, and turned to Elsbeth Ebertin (more) (1880-1944) the most prominent of the first female astrologers and a prolific author who had achieved fame after she drew up a horoscope on an unnamed person who was later revealed to be Adolf Hitler, and who had published a book on homosexuality in 1909 (Auf Irrwegen der Liebe) where she counted transvestites among a sixth group of homosexuals: those who are "all too in need of love", and who only stray into "sexual aberrations" out of the "exuberance of their feelings" or out of "sexual need".

Simon told Ebertin how she had wanted to be a girl since early childhood, had often had thoughts of suicide, transvested on the street, and how having been in love only three times, always with a woman, but often fantasized about love with men. Simon claimed to have been the editor of a transvestite magazine (but which one was not specified). The actual editors of Die Freundin had been incensed by the letter to Radszuweit, but otherwise supported Simon who was open about transvesting, freely used her name and provided photographs.

By 1932 Simon was completely impoverished and had had to close Café 4711. At the Essen criminal court 19 January 1932 Simon als Dame presented a Transvestitenschein. The charges of serving alcohol without permission, organising public dances and "insulting public officials in a way that was dangerous to the public" were upheld, but the charge of “groben Unfugs (gross mischief)” was dropped given that the accused had a Transvestitenschein. Simon was fined 25 marks.

Based on the letters and newspaper articles that Simon had provided, Elsbeth Ebertin wrote a pamphlet Mann oder Frau! Das Schicksal einer Abenteurer-Natur (Man or Woman:The Fate of an Adventurer's Nature) which told of Simon and included two photographs and was published in Hamburg.

After the Nazi takeover in 1933, Simon’s Transvestitenschein was cancelled. After a short prison sentence, Simon emigrated to Spain, but returned after the outbreak of the Civil War in 1936, and obtained work as a fitter.

23 October 1937 Anton Simon was charged by the Special Court of Stuttgart with “Heimtücke (insidiousness - political insult according to § 2 paras. 1 and 2 of the Nazi law of 20 December 1934)” having been denounced for criticizing the then government as idiots and rascals. Simon was sentenced to one year in prison – this was served in the Rottenburg am Neckar prison. 11 May 1938 Simon was granted amnesty on the basis of the "Law on Obtaining Immunity from Punishment" of 30 April 1938 and the remaining sentence was commuted to three years' probation. After release, Simon worked in a metal processing company.

Simon was convicted again and imprisoned for six months in the Welzheim police prison/concentration camp at the end of 1939.

|

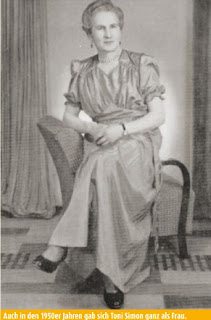

| Toni Simon in the 1950s |

Simon worked as a tester of high-voltage pylons. In this, and in the applications for reparations, she was referred to as Anton and Herr Simon. At the same time she was considered as a survivor of the pre-war queer scene in Stuttgart, and worked with the gay group Kameradschaft die runde which met in Stuttgart pubs. She arranged meetings and dances, and ‘Toni Simon’ was mentioned in advertisements in the local press. Her Transvestitenschein had been restored in 1951.

She supplemented her pension in the 1950s by smuggling in queer pornography from Denmark which at that time had a more liberal attitude to such publications.

Toni Simon died age 92.

- Toni Simon. „Angeklagter in Frauenkleidern. Die Welt der Transvestiten“. Die Freundin, 5,13, 1929.

- Elsbeth Ebertin. Mann oder Frau! Das Schicksal einer Abenteurer-Natur. Dreizack-Verlag, 1933.

- Rainer Herrn. Schnittmuster des Geschlechts: Transvestitismus und Transsexualität in der frühen Sexualwissenschaft. Psychosozial-Verlag, 2005: 140, 144.

- Raimund Wolfert: „Zu schön, um wahr zu sein: Toni Simon als ‚schwule Schmugglerin‘ im dänisch-deutschen Grenzverkehr“ Lambda Nachrichten 32, 133, 2010: 36–39. Online.

- Katie Sutton. “ ‘We Too Deserve a Place in the Sun’: The Politics of Transvestite Identity in Weimar Germany”. German Studies Review, 35,2, 2012.

- Julia Noah Munier & Karl-Heinz Steinle. “Wiedergutmachung von Transvestiten und Damenimitatoren nach 1945”. LSBTTIQ in Baden und Württemberg: Lebenswelten, Repression und Verfolgung im Nationalsozialismus und in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 21. Dezember 2017. Online.

- Karl-Heinz Steinle. “Toni Simon, geb. als Anton Simon”. Sie machen Geschichte: Lesbische, Schwule, Bisexuelle, Transsexuelle, Transgender, Intersexuelle, Queere, Menschen in Baden Württemberg.:22-3. Online.