Čháŋ Óhaŋ (c1840-1877) a Lakota Sioux, was given his father’s name of Tȟašúŋke Witkó on reaching maturity. He became a resistance fighter and war chief defending his people’s land against the invading Euro-Americans. He was one of the commanders at the victory of the Little Bighorn in 1876. He is known to the invaders as Chief Crazy Horse.

One of his grandchildren was Jacob Goodshot/Big Elk who was born on the Pine Ridge Reservation, South Dakota. He served as a military policeman at the National Airport in Washington and the Port of Embarkation in Boston. He married Maude Dowd of the Passamaquoddy/Peskotomuhkati nation in Maine, and they had one child who was born in 1937. Jacob died when the child was 13, and Maud and her child moved to Miami, where the young Goodshot’s ability as a comic strip artist was recognized and the Miami News ran the strip.

By 1954 Maud’s child was living as female, and had taken the name Jela St John Murphy. By 1956 they were living in East Greenwich, Rhode Island, near a naval construction station. Jela met a Navy Seabee from Michigan by the name of Cox. They fell in love. Cox soon realized that Jela was pre-op, but still wanted to marry her – which they did September 1, with the bride’s mother as a witness. The Navy recognised Jela as Mrs Cox and paid her a dependent wife’s allowance. All was going well.

However, in 1958, Maud declared that she was ‘fed-up’ with Rhode Island and wanted to live in the Mid-West. She insisted that Jela go with her. Which left Cox alone without his wife. So he deserted, and went to find her – which he did in Denver, Colorado. The Navy called in the FBI to find Cox, and their investigation discovered that Jela was not legally female. She was arrested in Denver. After a secret indictment by a Federal Grand Jury, Cox was arrested at his home in rural Michigan. Mr and Mrs Cox were both charged with conspiracy to defraud the Government over the wife’s allowance, a total of $548.40. Jela was charged under her male name. When released on bail, Jela told reporters that she had half-completed an autobiography. She also said:

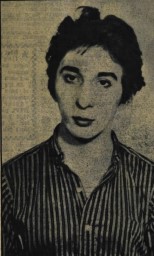

|

| Jela, 1958, after cutting her hair |

“I’ve been posing as a woman nearly four years. Before that, my life was miserable. Everybody made fun of me. Then when I changed over, nobody said anything. They accepted me as a woman”.

Cox was given a suspended two-year prison term, four years of probation and was ordered to repay the $548.40. Jela was given two years’ probation and ordered that she ‘undergo psychiatric treatment to bring out his masculine qualities’. She expressed a desire for genital surgery, but this was ignored. They were also ordered to separate.

What happened afterwards is not documented, apart from a few snapshots.

Maud and Jela moved to the San Francisco Bay area. Jela presumably completed transition. She married and changed her name with the US Social Security system in December 1962 to Jela Hicks.

In February 1967, Jela was arrested for drunken driving in Mill Valley, California and fined $100. Her past apparently was not discovered.

Maud Goodshot, described in her obituary as ‘beloved mother of Jela Goodshot-Hicks” died in San Francisco, June 1976.

In December 1980, the Hicks were injured but survived when their car stalled on a rail line and was hit by a six-engine freight train.

Jela died April 1989, age 52.

Thank you Bianca Zell for the research.

- “Chief Jacob Goodshot”. The Boston Globe, September 10, 1950: 18. Obituary.

- “Indian Youth Will Draw Comic Strip for Roundup”. The Miami News, Feb 9, 1951:31.

- “Arrests disclose Navy fraud case: He ‘wed’ female impersonator”. The Saginaw News, Oct 23, 1958: 12.

- “Impersonator Awaits Sentence; His life used to be ‘miserable’ ”. The Saginaw News, Oct 27, 1958.

- Barrie Harding. “John Got Married – to a Sailor”. The Sunday Pictorial, November 2, 1958: 19.

- Bill Jones. “Impersonator to take Psychiatric Treatment”. Denver Rocky Mountain News. Nov 22, 1958.

- “Judge Blasts Men’s Hoax of Marriage”. Spokane Spokesman Review, Dec 9, 1958.

- “Male ‘Bride’; Hubby Placed on 2-Year Probation”. Jet, 25 Dec 1958: 47.

- “Drunken Driver is fined”. San Rafael Daily Independent Journal, April 15, 1967: 30.

- “Goodshot, Maud Esther”. The San Francisco Examiner, June 15, 1976:32. Obituary.

- “Woman in good condition after car rammed by train”. Reno-Gazette-Journal, Dec 15, 1980: 3.

- Joanne Meyerowitz. How Sex Changed: A History of Transsexuality in the United States. Harvard University Press, 2002: 87.

Some accounts say that Jela was born and raised in Boston; others say a reservation in South Dakota.

The US average male wage in 1958 was just under $100 a week. So the secret indictment by a Federal Grand Jury was for only a few weeks wage.

What happened to Jela’s autobiography?